- Home

- Kim Aubrey

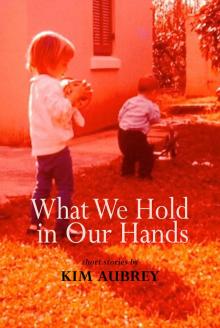

What We Hold In Our Hands

What We Hold In Our Hands Read online

What We Hold

in Our Hands

What We Hold

in Our Hands

short stories by

Kim Aubrey

DEMETER PRESS, BRADFORD, ONTARIO

Copyright © 2013 Demeter Press

Individual copyright to their work is retained by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for its publishing program.

Demeter Press logo based on the sculpture “Demeter”

by Maria-Luise Bodirsky

Printed and Bound in Canada

Cover photo: Diane Aubrey

eBook development: WildElement.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Aubrey, Kim, 1960-, author

What we hold in our hands : short stories / by Kim Aubrey.

ISBN 978-1-927335-33-8 (PBK.)

I. Title.

PS8601.U265W43 2013 C813’.6 C2013-907230-6

Demeter Press

140 Holland Street West

P. O. Box 13022

Bradford, ON L3Z 2Y5

Tel: (905) 775-9089

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.demeterpress.org

for my parents

Contents

Over Our Heads

Eating Water

Unfinished

A Large Dark

Lemon Curl

What We Hold in Our Hands

Compact

Flickers

Peloton

Outside of Yourself

Acknowledgements

Over Our Heads

THE NOVEMBER I CELEBRATED MY NINETEENTH BIRTHDAY, I’d already been married a year and was living in a high-rise apartment near the university with my husband, Cam, and our baby daughter, Alice. That was twenty-five years ago, but I still remember how the sun slipped away from the living-room floor while we waited for Cam to return from his last class of the day, and how Alice would grab hold of my shirt or my long straight hair and hoist her body up, toes pushed into my thigh, face against my face, as she squealed and pointed at the china dolls banished to the top of the bookcase.

My mother had collected them for me on her antiquing expeditions in Southern Ontario and Northern New York State. Too bad she kept the dolls, whose dazed chalky faces used to give me nightmares, but threw out the superhero comics I’d loved to read, their strong black lines and simple flat colours constructing a world where help was only a page away.

If I didn’t lift Alice to see the dolls, she’d try to climb onto my shoulders. As she strained upwards, I could see the long train of days stretching ahead, with me helping her to get the things she wanted, while my own dreams and desires receded into the distance. And I remembered staring at the “No Deep Dives” sign posted on the wall behind our high school pool, how the fine hairs on my arms used to rise and tug at my hungry skin, urging me to plunge in headfirst.

One day when Alice and I were out walking our familiar route along Bloor Street, she reached towards an empty paper cup on the sidewalk ahead, leaned forward in her stroller, and flexed her fingers wide as if she could see, taste, smell, and hear with them. Then, in one fluid movement, she dove out and struck the pavement.

I scooped her up. Her nose was bleeding and she was bawling. I started to wail with her, devastated at my failure to protect her. I’d buckled the strap that held her in, but must not have pulled it tight enough.

Pushing the empty stroller, I carried Alice to her doctor’s office in the next block. Even living in the big city, our world was small, everything within walking distance, just like back home.

The doctor cleaned her face and said she was fine. The next day a violet bruise spread across the bridge of her nose, fading to a green smudge by the end of the week. When we went walking, people looked from Alice’s nose to my face and tagged me as an irresponsible, or maybe even abusive, teenaged mother, like the ones you hear about on the news, who leave their toddlers alone overnight while they go dancing, or let them play next to twelve-storey-high open windows, or shake them until their brains are scrambled and they stop crying.

Whenever I heard those stories, I imagined a superhero swooping in to rescue, not only the babies, but the mothers too. By carrying them away from the scene of neglect and desperation, by setting them down on solid ground, she would somehow transform and restore them, leaving them better able to cope.

Cam and I were coping, keeping Alice safe and healthy. I cooked her chicken livers and brown rice. Cam stuck safety plugs into the electric outlets and made sure the windows and balcony door were always locked. I took Alice to every checkup and monitored the temperature of her bath water, never letting my eyes stray from her while she was in the tub. But often I cried from sheer exhaustion and longed to be transported to Paris or Vienna, where I imagined myself eating brioche and jam in an outdoor café while discussing books and art with dark-eyed, bearded men.

That November, as my birthday approached, and these daydreams became more frequent, I discovered an Austrian café on Bloor Street where I could sit for half an hour with a cup of sweet coffee before Alice grew bored with her toys and the bites of pastry I offered as bribes. I watched her taste chocolate and almond paste for the first time, puzzlement, delight, or disgust blooming in her blue eyes. When she grew restless, I’d take her for long walks, window-shopping and browsing for books through the cool, dull, darkening afternoons.

It was on one of these walks that I saw a guy I’d known at home, a boyfriend of my older sister, Ellie. Alice had fallen asleep in her stroller, and I’d wheeled her into a bookstore out of the cold when I saw him. Jackson used to hang around our house or drive us into town where we’d watch a movie—my brothers and I sitting near the front while Jackson and Ellie sat in the back making out. You’d have thought Ellie would’ve been the one to get pregnant and marry young, not me. Back then, she never seemed to have a thought in her head that didn’t involve boys or clothes. But now she was at teacher’s college, sharing a house with a group of women who didn’t shave their legs or wear deodorant, and here I was, a mother and wife, spritzing my wrists with free perfume every time I walked through the first floor of The Bay.

Jackson looked different from how I remembered him—sitting expressionless on our family’s living-room couch, watching TV with Ellie wedged up against his side. Now he was reading a Penguin paperback, his face unshaven, brown hair long and wavy, tucked behind one ear so that he could see the page. He looked like any other university student in his heavy knit sweater, army pants, and running shoes, except more real and somehow larger than life, because he was from back home, and I hadn’t expected to see him here.

Parking the stroller across the aisle, I picked up a book from the discount table, peering at him as I flipped through Joyce’s Dubliners. Then, reading, I forgot about Jackson until I felt a hand on my back and looked up into his bloodshot eyes.

“Janelle? I thought it was you.”

“I saw you reading, but I didn’t want to disturb you.”

I could smell the lemony perfume I’d sprayed on at The Bay and the mixture of cigarette smoke, marijuana, and perspiration escaping from his sweater. A pattern of X’s crossed his chest over a pair of canoe paddles also crossed. I shook my head a little to make my dark hair ripple.

“I wrote a paper on Joyce’s stories.” He ducked his head

and scratched his chin the way he used to when he was unsure of himself or talking to one of Ellie’s lip-glossed girlfriends.

“I thought you were in Montreal,” I said.

“Not anymore. I’m doing my Master’s here.”

I felt young and stupid, afraid to say the wrong thing.

“How’s your sister?” he asked.

“She’s at Western in teacher’s college.”

“Those days seem long ago, don’t they, kid?” He always used to call me kid and ruffle my hair. His hand rose, then stopped.

“Do you want to go for coffee?” I asked, inspired by a vision of the two of us sitting in the Austrian café discussing books.

He frowned at Alice asleep in her stroller. “Will she be okay?”

My face grew hot. Alice hadn’t figured in my café vision. Jackson must have heard about my pregnancy and marriage. When you’re from a small town, you hear everyone’s news whether you want to or not.

“She’ll be okay for a while,” I said, wondering whether he was concerned about Alice making a fuss in the restaurant or worried about her welfare—the smoky atmosphere, the adult conversations.

That was the beginning of my friendship with Jackson. I don’t count the old days at home when I was just a kid, and he was the cool, cute boyfriend of my older sister, although Jackson claimed that even then he’d found me interesting.

“You used to ask the strangest questions out of the blue,” he said later at the café, his fingers trailing across his beard. “And your eyes seemed full of knowing and of wanting to know.”

“I used to study you, wondering what you were thinking,” I said.

My coffee tasted especially sweet and bitter that day. Cam never said things like that about my eyes. He used to tell me I was beautiful, but now he never did. He was always busy. We both were, except that my busyness included a lot of hanging around with Alice, during which I could either tune out and daydream, or worry about my life—how much it had changed, how Cam was sometimes too tired to make love, how we weren’t even twenty yet and we were like two old fogies sitting in front of the TV, watching other people pretend to live exciting, dramatic lives.

Already as I looked across the table at Jackson, I could foresee the potential soap-opera scenario of my life—handsome poet from her past sweeps Janelle off her feet. Her doctor husband suspects something, catches them together, and punches handsome poet in the jaw. Tears and apologies follow. The couple patch things up but the lover never disappears for long, returning in different guises, offering new temptations. I told myself I didn’t want a part in that scenario, that what I wanted from Jackson wasn’t sex so much as literature. He talked to me about Joyce’s characters, how they were conflicted, loving Ireland but wanting to escape her. How Gabriel in “The Dead” suddenly sees himself as he is—coarse and compromised, unable to compete with the pure strong love of dead Michael Furey.

Alice slept in her stroller for an unprecedented hour and a half. When she woke, she stared at Jackson and bawled, going through stranger anxiety right on schedule, according to the Dr. Spock book my mother had given me. I lifted her, comforting myself with her warm body and hot tears. All through coffee, even though I’d told myself it wasn’t what I wanted to happen, I’d longed to pull Jackson close, to feel his bristly face on my lips, his hot, sweet breath on my neck.

“We have to go,” I said.

“Say hi to Cam for me.” Cam’s older brother, Dan, had been Jackson’s best friend in high school. The smallness of our town used to make my bones ache to be out of there.

Friday and Saturday nights, Cam waited tables in a nearby restaurant while I stayed home, reading Alice stories from The Richard Scary Omnibus and splashing with her in the tub. I’d dry her plump body with a soft towel, rub her hair until it stood in curls, then dress her in a fuzzy cotton sleeper. After I’d nursed her, if she settled down to sleep in the crib beside our bed, I’d make myself a cup of tea and watch old movies until Cam got home, but if she fussed and whimpered, or screamed and screamed, her face growing redder by the minute, I’d become frantic not knowing how to help, begging her to stop, frightened by my growing desperation.

One such night, I bundled her into the stroller. As soon as we entered the dim hallway outside our apartment, her crying eased into hiccups. I walked her through the city streets to the restaurant where Cam was working. Holding her up to look through the window, we caught a glimpse of his tall figure in white shirt and maroon vest balancing plates of food over his head.

“Da Ba.” Alice pointed at him, the first time she’d found a name for either of us.

“Yes,” I said. “Daddy.” I was in no hurry for her to call me Mama. I thought it would give her an added power over me. Now I know it was the separation I feared, how the knowledge that I was a person separate from herself might open the way to blame and resentment such as I’d felt for my own mother.

On our way there, I’d imagined sitting with Alice at an empty table, eating a slice of apple tart while waiting for Cam to finish, but all the tables were full and he was so busy that I knew he wouldn’t be happy to see us. As we watched him disappear into the kitchen, I thought about Jackson, how we’d lingered over coffee that afternoon while rain blurred the café windows, and the sky darkened.

That night Cam arrived home exhausted and fell into bed beside me, but I couldn’t sleep. My chest was heavy with feelings I wished I didn’t have, and I longed to cry like Alice until my face was red and I woke the whole building.

Saturdays, I worked in the university library shelving books, while Cam stayed home with Alice. I liked the earthy smell of the stacks, where I rolled a cart from aisle to aisle, picking up abandoned books on the way, stopping sometimes to pull out a slim volume of poetry or a hefty history tome. I’d pass a hand over their woven covers, slip my fingernail into the close-pressed pages, flip them open, and read whatever words presented themselves, as if they had something crucial to tell me at that particular moment, like a friend who has to talk to you right away.

Jackson and I didn’t arrange to meet again. We simply hung out in the same places. He looked for me at the library and became a regular at the café, where he settled in for the afternoon with his books and papers. Alice liked to sit in his lap and rub her hands across his rough cheek. I watched with envy, imagined his beard scraping my own curious fingers. When she grew tired of this, she’d climb up him to peer over the back of the bench at the people in the next booth, charming them with her gap-toothed smile. To win back her attention, Jackson would draw faces on the tips of his fingers with a ballpoint pen, moving them like puppets while he made noises that ranged from a growl to a squeak.

During the winter, Alice learned to walk. I always knew it was time to leave the café when I spent more time chasing her than talking to Jackson. He never seemed to mind our clutter—the hats, scarves, mittens, juice bottles, toys, and storybooks—or the interruption to his writing and reading, or that when we ordered crêpes with jam and chocolate, Alice managed to smear all our faces with something sticky and sweet.

I pulled baby wipes from her diaper bag, handing one to Jackson, who dabbed at his beard, missing the orange jam stuck in the bristles.

“Here.” I leaned across the empty plates, reclaimed the wipe, and carefully stroked the jam from his chin.

Cam spent most of his days in science labs, classes, or the library. When he could, he came home for lunch. He’d swoop up Alice and twirl her around. Or lift her onto his shoulders, galloping about the apartment, ducking at each doorway. As her head passed under the doorframe, her gleeful smile would shift to a brief worried suspension of breath, and I’d find myself holding my own breath, wondering if I’d been reflecting her worry, or if she’d caught mine.

Cam and I ate canned soup and grilled cheese while we watched the midday news, then reruns of The Flintstones. Our small table sat beside the kitchen, dia

gonally across from the television where Fred yelled for Wilma, who served up enormous slabs of ribs. Lulled by the cartoon’s familiar sounds and images, we took turns opening blue-lidded jars and spooning strained carrots and pulverized chicken into Alice’s eager mouth.

“I like it when you come home for lunch,” I told Cam.

“Me too.” He held out a finger for Alice to grab. His shaggy blond hair fanned out from walking through the wind. A too-small tan sweater stretched across his chest. Tiny holes had worn through the wool at the edge of the neckband and under the arms. When he smiled at Alice, his blue-grey eyes looked warm and tender like they used to when we were dating.

I draped my arms over Cam’s shoulders, nuzzled his neck.

“That tickles, Janelle,” he said, shaking me off.

“Let’s sit on the couch for a while before you have to go back.”

“What about Alice?”

“Alice is fine.” I lifted her from the high chair, washed her face and hands, and set her down on the carpet to crawl. “Come on, Cam,” I said.

He was standing, weight on the balls of his feet, staring out the big window as if ready to soar out and over the city. I reached my arms around his chest and squeezed. He lifted me so that my legs dangled.

“I wish you could spin me around like you do Alice.”

“Your feet would hit the window and the shelves.” He kissed me once on the lips before setting me down.

The way his eyes flitted past me, I could see his mind already clicking forward to the chemistry lab. I picked up Alice and held her close. She squirmed in my arms, reaching for Cam, who kissed her goodbye twice on each fat cheek.

When he left, she started to cry. She always cried when I went to my evening linguistics class or to work, but this was the first time she’d cried for Cam.

“Daddy will be back soon,” I said, rocking her, offering a breast, unaware that, in a few years, she’d cry even harder, clinging to me as I left her at nursery school, screaming for a father she wouldn’t see for months at a time.

What We Hold In Our Hands

What We Hold In Our Hands